World-Renowned Angling Destinations Are Literally Sinking into the Gulf of Mexico

Historic flooding focused the nation’s attention on South Louisiana a little more than a month ago, as more than 100,000 homes and businesses were inundated by as much as 30 inches of rain that fell over a three-day span.

Streets and neighborhoods far removed from boundaries on federal flood maps became angry lakes and frenzied streams. All of that rain ripped and clawed its way into drains, ditches, bayous, and rivers and, when those couldn’t contain the deluge, water rushed back out the through banks of those waterways and into people’s homes.

In the weeks since that unprecedented rainfall, some South Louisiana communities that were unaffected by the massive downpour have flooded, as well, though it’s doubtful the rest of the country heard much about it.

Small coastal fishing towns like Cocodrie, Delacroix, Leeville, and Dulac flooded, not because of storms that actually made landfall, but simply because the wind blew hard out of the southeast for a couple of days and a tropical system hit hundreds of miles away.

Flooding that covers roads and docks and water creeping into yards, under homes and camps, has become pretty routine for those who live in those towns or visit local marinas to launch boats in pursuit of speckled trout, redfish, flounder, and bass. It happens every couple of months.

Why So Water-Logged?

The Gulf of Mexico is rising, as is every other sea and ocean. In that respect, the threat of increased flooding is not unique to Louisiana’s coast. But what does separate Louisiana’s coast from that of its neighbors is the constant, menacing subsidence—this means that, for a variety of geological reasons, the land, created by millennia of sediment deposits from the Mississippi River, is slowly but surely sinking into the Gulf. The combination of rising Gulf waters and receding land mass, called relative sea-level rise, means Louisiana’s coastal towns are feeling the impact of higher water sooner and more frequently than other parts of the Gulf region.

This is not breaking news to coastal residents, who have had to elevate homes over the last two decades to keep their feet dry. Scientists and engineers are keenly aware of the threat, and are trying to design and build wetland restoration projects and extensive flood-protection systems to help shield New Orleans, Houma, and other coastal Louisiana cities from hurricane storm surges.

An Intensifying Threat

It was recently revealed by the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority—staff working on the state’s revised coastal restoration Master Plan, due out in early 2017—that the latest models show relative sea-level rise may claim much larger swaths of what’s left of Louisiana’s coast over the next 50 years than previously predicted. The last time Louisiana’s blueprint of projects to restore critical habitat and protect coastal communities was updated in 2012, coastal engineers, planners, and wetland ecologists predicted that the worst-case scenario for areas south, east, and west of New Orleans was two to four feet of relative sea-level rise.

Now, those models indicate that might be the best-case scenario for those same areas, and as much as six feet or more of average sea-level rise can be expected in the coming 50 years.

That is sobering news for those optimistic about the future of one of the world’s most fertile areas for fish and wildlife, and the communities that provide access for hundreds of thousands of anglers, hunters, and commercial fishermen. If the models are correct, Louisiana towns like Venice and Shell Beach, renowned as world-class angling destinations, may be more submerged than they are dry—or worse, simply uninhabitable, even with elevated homes and businesses.

Levee systems will be pressured more and more as water regularly laps at their bases. The rebuilt marshes that were supposed to provide protection to the levees and help restore the critical nursery grounds for fish and their forage could succumb to more frequent wave action and saltwater intrusion. And rivers, like the ones overwhelmed by the August rains, and even the Mississippi, will increasingly struggle to push their way into coastal lakes, bays, and eventually the Gulf.

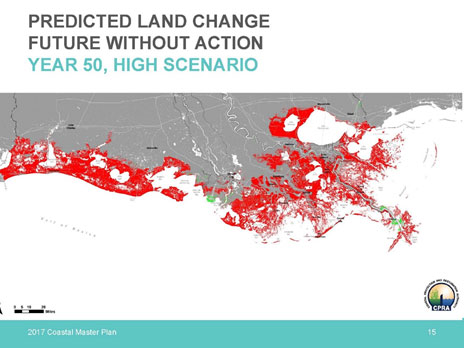

In the diagrams used by coastal planners to show the expected results of relative sea-level rise (above), red ink means land lost, while green demonstrates where sediment deposits will create new wetlands. Unfortunately, those diagrams look like a Santa Claus suit with a single sprig of mistletoe stuck to it.

But those charged with creating these models are quick to point out that this picture represents a future without action. This is what could happen if we do nothing. The upcoming plan includes projects to create marsh, elevate homes, and protect communities that could put a lot more green on the map.

A $20-Billion Opportunity

The settlement with BP over the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil disaster will bring as much as $6.8 billion to Louisiana, and $20 billion in all to the five Gulf States, over the next 15 years. That money will be used to restore and enhance coastal ecosystems and local economies, meaning Louisiana’s coastal planners have their best opportunity yet to take action to address sea-level rise and land loss.

A draft of the 2017 Louisiana Coastal Restoration and Hurricane Master Plan will be released in January of 2017, and the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority will accept public comments when the draft is released. We’ll let hunters and anglers know when they can make their voices heard on this important step in the planning process.

For more information about the master plan and the effort to restore Louisiana’s coast, please visit the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority website.