These Changes Are Worth Your Time to Stop the Spread of Chronic Wasting Disease

As deer hunters, we will inevitably have to change our habits to prevent the spread of CWD—how much are you willing to give up so we don’t have to give up on hunting altogether?

We know by now that chronic wasting disease has infected deer species in 25 U.S. states and two Canadian provinces. It is always fatal, spreads rampantly, which, unfortunately, demands that hunters make at least some sacrifices if we hope to curb the epidemic and save deer hunting as we know it.

CWD has most recently made a pass through the upper-Midwest states where I live and hunt. That makes this disease not only detrimental at a population scale, but also deeply personal for me. I don’t believe that hunters are more averse to change than the average group of people, but we’ve often been asked to change our ways for the good of the herd or landscape.

The good news is that we’ll be at the forefront of the effort to control this destructive disease. The bad news is we’ll also have to be at the forefront of change, no matter how uncomfortable.

How much should we be willing to sacrifice? If you ask me, quite a bit.

CWD Directly Threatens the Places Where I Hunt

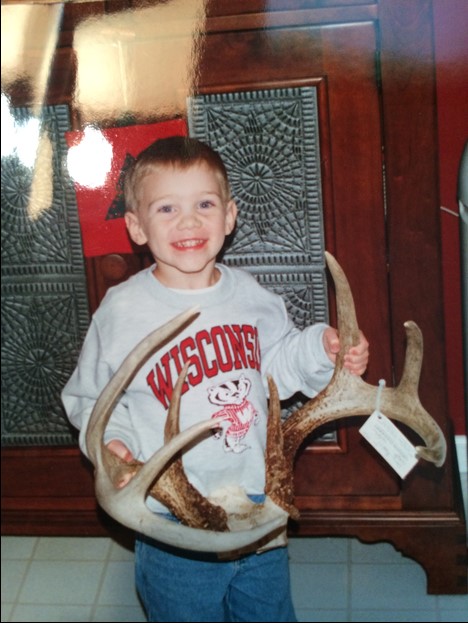

I have been hunting in Michigan since I was five years old, at which point I convinced my dad to build us a deer blind and take me along with him. Back in those days, we started “hunting” with a camera, a Stanley thermos of hot chocolate, and, on his part, a whole lot of patience for a squirmy kid. Since then I have upgraded to a 12-gauge slug gun and Folgers, but we still sit on that same stone pile every November. Three generations of Boohers hunt together on an old family farm in the southwest part of the state every year.

Most of the other hunters that I know have a similar story.

I’ll be honest, there are better places to hunt. And we might look for one if our only goal was a deer with 130+ inches of antler. Don’t get me wrong—harvesting a trophy buck would be nice, but it’s not essential, and truthfully it hasn’t happened in quite a few years on this property. But we take the time of work and school, make the drive from Wisconsin, and pony up for out-of-state licenses just to carry on a tradition that is at least four generations old.

My time afield is about more than just deer and deer hunting. It’s about spending quality time outside with my family, knowing where my food comes from, and intentionally taking time to be away from the rest of our busy lives.

The deer are just a part of it, but these experiences wouldn’t happen without them.

Fortunately, Hunters in North America Have Done This Before

One of my biggest fears is the permanent loss of wild deer herds and, therefore, my inability to share my family’s traditions with another generation of whitetail hunters. So it’s worth it to me to make broad, individual sacrifices today to ensure the preservation of this resource for the future.

In the words of the famed conservationist and forester Gifford Pinchot, it is our responsibility to practice “foresighted utilization, preservation, and renewal of forests, waters, lands, and minerals for the greatest good of the greatest number for the longest time.” That is what we as hunters must do with regard to elk, moose, caribou, whitetails, and mule deer.

Of course, this is not a new concept, especially in the field of wildlife conservation. This sentiment dates back many years before the famed North American conservationists of Theodore Roosevelt’s tenure. The story of hunters acting as conservationists in North America is long and detailed, and it must inspire our future actions.

Since the late 19th century, we as hunters have stepped up to change our policies and practices for the betterment of the wildlife resources that we so enjoy. Examples of sportsmen and women willing to do this work are abundant among TRCP’s partners: If waterfowlers had not banded together to form Ducks Unlimited during the dust bowl, we likely would not have been able to have duck seasons today. The same could be said of the National Wild Turkey Federation’s efforts to reintroduce and propagate a game bird that was once extirpated from much of the Eastern United States. The Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation did the same for elk.

Unfortunately, today we are faced with a familiar, yet overwhelming challenge—to save our wildlife in order to sustain our traditions. For the sake of the habitats that we know and love, and the generations of hunters that are to come after us, we must actively change our habits. And with respect to CWD, that means a few things:

1. We need to be more conscientious about moving deer carcasses, especially “sensitive deer parts.”

These include the brain, eyes, spinal cord, lymph nodes, tonsils and spleen. Yes, this might impact your ability to bring your trophy home to your favorite local taxidermist or processor. However, there are ways to support the businesses near your home and slow the spread of CWD. The easiest way to do this is to hunt near your home, but that is not an option for everyone. If you hunt out-of-state or in another part of your state, consider doing more of your own processing in the field or having at least a portion of it done wherever you’re hunting.

Plan to add a few more knives, a bone saw, and a big cooler to your list of hunting gear so that you can bone-out your kill on-site.

Many states with CWD, like Michigan and Wisconsin, and some without, like Tennessee and North Carolina, are starting to restrict the importation of whole carcasses from other parts of the country. However, most allow deboned meat and finished taxidermy products to be brought in. States have banned these body parts to prevent the spread of prions, while also allowing hunters to bring home some of their trophy for the freezer or the wall. These policies require some more planning and effort on our part, but are very important in minimizing the spread of this disease. Be sure to check out the regulations in the state where you live before you head out this fall.

2. We need to think a little harder about bait piles and salt blocks.

Every corner bar where I live has peanuts on the counter, almost without exception. I hardly ever think twice before grabbing a handful, that is, until the person next to me starts hacking and coughing, or worse, sneezes into the bowl. How about you? Would you partake if the person next to you is sick? How about if you knew that a quarter of the people in the county are ill?

Is this all that different from deer feeding on a salt lick or a pile of corn? In Dane County, Wisconsin, where I live, upwards of 25 percent of the whitetails are estimated to be infected with CWD. The only difference: as far as we know, they can’t tell who is sick and who isn’t.

Feeders are a great way to bring a lot of deer to your stand and can make for a much easier hunt, but they are also a key vector in the spread of disease. Concentrating animals (or people, for that matter) will make any disease spread more rapidly, but this is especially true of chronic wasting disease.

Unlike a large food plot or a stand of mast-bearing trees, mineral blocks and piles of corn bring deer to very, very specific locations. These lures force deer to eat off of the same exact spot as other deer. With a disease that is spread through saliva, like CWD, these places become huge transmission vectors.

In addition to increasing harvest limits in disease management areas, most states are changing some of the baiting rules that hunters must follow in the field. This includes restricting the use of urine-based lures, feed piles, and mineral blocks. While these bans often mean more time in the field, they are critical to slowing the spread of CWD. Each of these attractants can facilitate the spread of the disease by congregating deer in a specific area. As more cervids gather in these areas, there is a higher likelihood of an infected individual being present and transferring prions to other individuals or shedding them in the soil or water nearby.

3. We have to get our deer tested by state wildlife agencies.

Some hunters, and you can likely name a few, are reacting to policy changes and appeals for testing— implemented by state wildlife agencies to control the spread of CWD and improve our hunting—by railing against the effectiveness of wildlife managers. But these organizations are responsible for, and have a vested interest in, maintaining healthy and productive populations of game species.

As a hunter and someone who is studying to be a certified wildlife biologist, I feel that it is our responsibility to provide them with as much information as they might need to effectively and efficiently achieve these goals.

I get it. It’s a pain. It might take a little extra time and another $5.00 in gas to get to a check station, when all you really want to do is go home, eat some chili, and take a shower. Please, this season, before you go home and put your feet up by the fire, take your deer to a local check station to have someone from your state wildlife agency take the lymph nodes from the deer.

These small glands in the neck are easy to remove and they will not take your trophy antlers. The technicians at these stations are also trained to do these tests without damaging the cape of your deer, and often they will provide extra services like aging or green antler measuring at the same time.

Despite warnings from the Center for Disease Control and the World Health Organization, some people still choose to eat venison from untested deer in infected areas. Even if you are comfortable doing so, it is critical for state wildlife agencies to have as much information as possible about the deer in your area.

In the grand scheme of things, these steps seem like a relatively small price to pay for the future of deer hunting and the chance to sit in a blind with my future kids or nieces and nephews.

I will be making a few changes this November. Will you join me?

EDITOR’S NOTE: The TRCP says goodbye to our fantastic policy intern, Charlie Booher, this week. We wish him well in his final few years at Michigan State University, and we can’t wait to see where his passion for fish and wildlife takes him.

SHARE ON

You may also like

The role corn plays for gamebirds and economies ac...

Sportsmen’s conservation policy issues from publ...

Sportsmen’s conservation policy issues from publ...