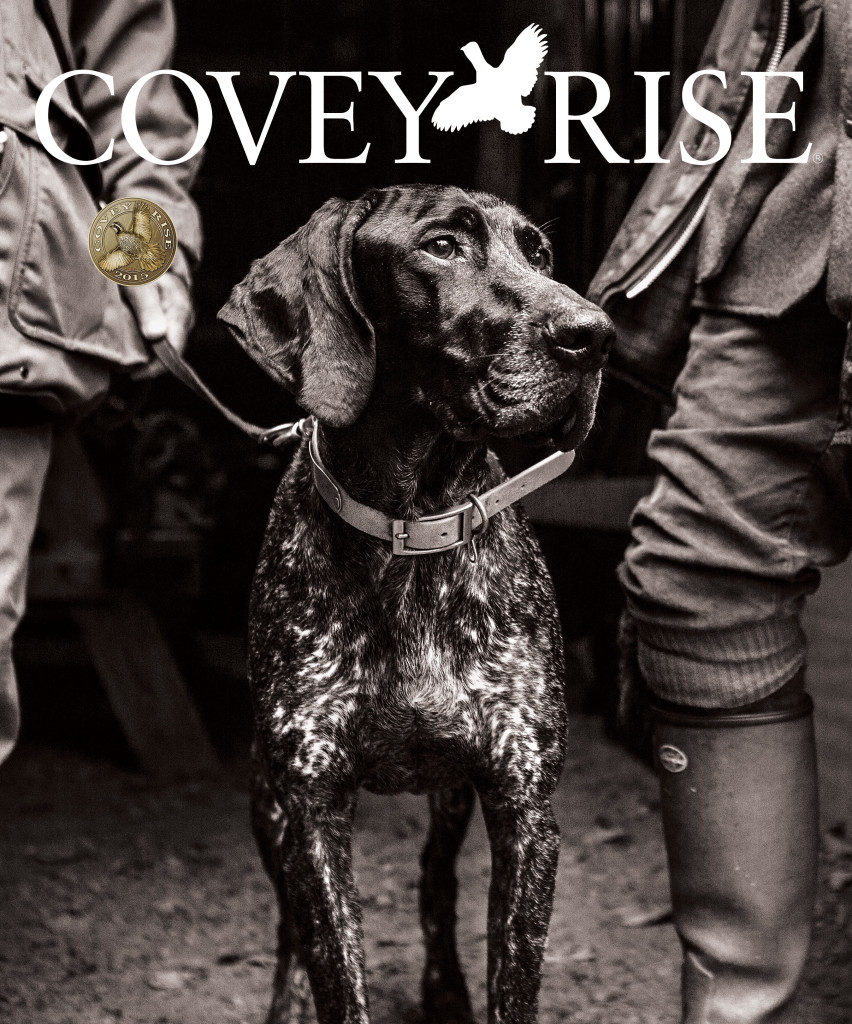

Ryglen

One of the many wonders of bird hunting with a dog is that rare moment when you get to witness a living being doing exactly what it is wired to do. When a pointer, for example, catches scent of a bird in midair and turns back around on itself to land, locked up, flared nose to quivering tail, eyes on the prize. Or when a seasoned retriever under the cover of a duck blind follows birds in the air with slight movements of its head, offering only a faint snuffle to cue the guns as the ducks cup and commit, waiting patiently for the harvest before launching enthusiastically into icy water to live the dream.

These are the moments that connect us with our best friends and hunting partners, but they also remind us of that simple innocence of childhood, before mortgages and conference calls, when walking afield with a good dog and a trusty shotgun was the beginning, the middle, and the end of a great day. For many of us, hunting is what we were wired to do—at least until we grew to adulthood and found out we were actually wired to sit through meetings, diagnose plumbing issues, and navigate spreadsheets instead of that old pickup truck we left behind in our youth. Sometimes it takes a well-trained dog, hunting in the zone, to remind us of our original wiring. That, or a good dentist.

From those childhood days hunting birds with his uncle, Jay Lowry felt a connection with bird dogs, and he’s quick to add that his heroes have always been dog trainers.

Jay Lowry, by all accounts, is a good dentist. His childhood neighbor in Vandalia, Illinois, was a dentist, and that seemed like a good career choice when Jay was heading off to college. There was a living to be made and people to help and responsibilities to accumulate, like a wife and children. So off he went, filling cavities and collecting the accoutrements of adulthood with all deliberate speed, all the while losing sight of his earliest dreams. If there was an anthem for frustrated adults, it would be playing in the background right now. Most people have sung a chorus or two, at the very least humming along as the life they envisioned is displaced by the life they’ve created. And the sight of a hunting dog happily doing exactly what it is wired to do can be both exhilarating and excruciating, depending on how loudly that anthem is playing in your head at the time.

Lowry suggests that we see this behavior more in dogs and other animals “because humans are too smart, and we talk ourselves out of doing what we are wired to do.” So why does this message resonate so clearly with this particular dentist? Because Jay Lowry is wired to train dogs, and his road to reconciling his dreams with his dentistry is at once compelling and inspiring, once you get past the flossing and rinsing.

A Knack and a Passion

A hand-carved and fading wooden sign above the door of Ryglen Gundogs reads “Lowry’s English Setters” and serves as a lasting artifact of Jay’s youthful ambition and early connection to dogs and their training. The sign commemorates his raising a litter of setter puppies while still in high school. From those childhood days hunting birds with his uncle, Jay Lowry felt a connection with bird dogs, and he’s quick to add that his heroes have always been dog trainers. Granted, dentists are rarely cast in a heroic light, but dog trainers? Lowry suggests that “dog training is actionable communication,” and, as a kid, he recognized cause and effect. If he worked with dogs on specific skills, they would respond and reward his efforts. As life would have it, though, that palpable affirmation of early skill and enthusiasm was soon washed away by the ebbing tide of opportunities and expectations.

The dog-training tide began to rise again after dental school, and more than a decade ago, Lowry responded to a magazine ad and bought his first dog as a working adult. Duke, a Wildrose Kennels Lab, garnered every waking moment of Lowry’s time away from the dental office. The goal was to train an extraordinary duck dog, but, more importantly, Lowry was excited to be back in the routine of training a dog.

Guiding him along the Wildrose Way was Mike Stewart, a mentor and partner in what might be described as Lowry’s graduate education in dog training, including an early role as associate trainer in the Wildrose network of trainers. Over the course of the last 10 years or more, Jay Lowry has honed his training skills in substantive ways, though he trained only Labs for most of that time. That all changed in 2013.

A Royal Quandary

Lowry accompanied Mike Stewart on a three-day, whirlwind tour of the United Kingdom in early 2013, and along the way he renewed his acquaintance with Nigel Carville, a Wildrose partner from Northern Ireland, and met Ian Openshaw, a renowned trainer and purveyor of English cocker spaniels with more than 100 field-trial champions to his name. While that’s a record that will likely remain unchallenged, Lowry was even more impressed when Ian clapped twice and an eager cocker spaniel leapt into his arms and looked around excitedly. It was the face that launched a thousand shifts.

These transitions began with Cassie, the first dog Lowry imported that same year from Rytex Gundogs, the kennels owned and operated by Ian and his wife Wendy in Shropshire, England. With field-trial experience and championship lineage, Cassie would hunt all day and ask for more. Next came Zak, a field-trial winner and accomplished hunter who, together with Cassie, sired the first of Lowry’s litters.

The budding kennel needed a name, and Lowry returned to the British roots of his stock to import the new title, Ryglen, from Openshaw’s Rytex and Carville’s Astraglen. Our friend the dentist found himself in the smiling jaws of the dog business, and his puppies were finding their way to homes across the country. His was a hobby gone wild.

And the champions kept coming, including, most notably, Pop, a field-trial champion and mother to Diamond, hunting companion to Her Majesty, Queen Elizabeth II. Yep. That Queen. This auspicious arrival prompted a bit of an experiment, when Lowry was able to recreate, through artificial insemination, the original union that produced the Queen’s dog Diamond. The result was Charlotte, a sprightly young lass with an extraordinary pedigree but no place to go.

Herein lies the quandary. Ryglen Gundogs prides itself on extending the traits and bloodlines of field-trial champions, and young Charlotte, while of royal birth, would have to travel and train across oceans to achieve that status. And let’s face it, England is a long trip for a little girl from Brownstown, Illinois. No word yet on how those passport photos are coming along.

A man of strong faith, Lowry muses about being the curator of a divine gift, a deeper connection to his avocation that fuels his desire to grow and improve.

A Dream to Sink Your Teeth Into

While Lowry admits that he’ll always keep a Lab as long as ducks are flying, and that pointing dogs retain an almost nostalgic appeal that reminds him of the quail hunting of his youth, he’s fully invested in the English cocker spaniel worldview.

“I’ve never seen a dog enjoy hunting as much as a cocker,” he says. “You have to smile when you watch them work and, ounce for ounce, they outwork all other dogs.” And that sense of peace seems to be at the heart of his passion for the hard work of dog training. Remember, this is a man who practices dentistry four days a week with every other minute, it seems, dedicated to daily dog maintenance and training. Add to that mix a wife and young children and it can, at times, be a struggle to balance the urgent with the important. And yet he perseveres with the energy and enthusiasm embodied in his own dogs. He works hard and he’s happy to be here.

A man of strong faith, Lowry muses about being the curator of a divine gift, a deeper connection to his avocation that fuels his desire to grow and improve. To facilitate that growth improvement during a particularly trying time of tension between dentistry and dogs, Lowry sought the advice of a life coach, someone who could look at his twin pursuits objectively and help him better balance his work life and what he viewed as his life’s work. As Lowry wandered through his own hour of darkness in Gethsemane, the outside observer offered a point of clarity and lasting reconciliation. He suggested that Lowry surround himself with dogs in his office, to let his passion more completely coexist with his profession. This epiphany led to pictures of dogs on the walls of treatment rooms instead of the more typical medical representations of teeth and endless smiling faces. The dogs on the walls had a calming effect and offered natural talking points between patients and caregivers. The transformation integrated Lowry’s competing worlds and fostered a sense of serenity.

An even more consummate peace of mind emerged from the same exercise. Dog training and the resulting performance afield offer Lowry an affirmation that dentistry simply can’t. Nobody looks up from a reclined exam chair with picks and mirrors in their mouth and mumbles, “You’re a great dentist!” The absence of those sentiments might help explain that profession’s historic stronghold on the suicide list’s top spot. That gratification, immediate or otherwise, can be an important part of life’s satisfaction. It is, after all, that human feedback, from ourselves and others, that helps us navigate the world and identify our place in it.

In his work with dogs, Jay Lowry sees living creatures doing what they are wired to do. And in living his childhood dream, this small-town dentist is doing a pretty good job of that himself.