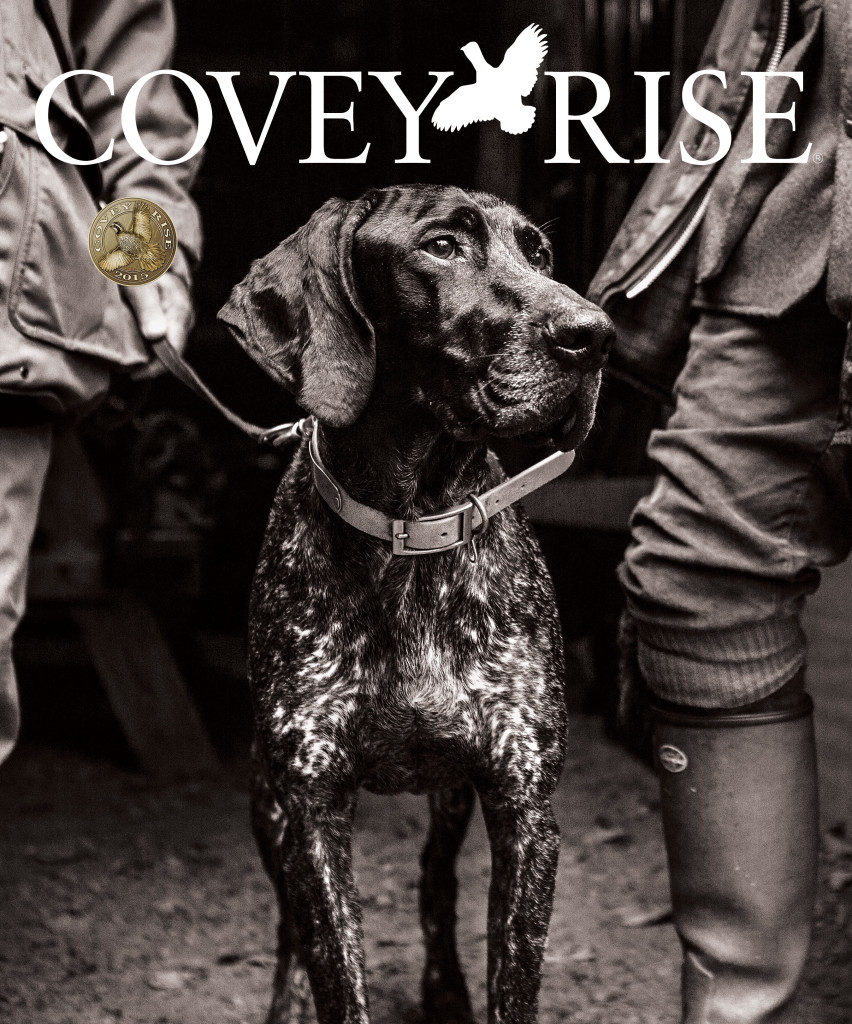

Ever wonder what goes on between the time that I point the birds and when you show up? I’m thinking of that delicate moment in the grand upland pageantry, the one when I’m nose to beak with a bevy of birds, and you’re making your way from the Jeep, or trying not to fall off the horse, or maybe offering last-minute instructions to the tourists clad in the latest britches and shirts—all clean and fresh with the original creases still intact—while loading shells from their first box afield. For you, it may seem like a nanosecond. After all, you’ve got a dog on point and the promise of feathered chaos and a money shot.

But I’m the dog, with a characteristic weakness for chronology, standing completely still with my hypersensitive sniffer thrust in the general direction of something fowl smelling. The quiver in my extended tail belies the notion that I am in control of my emotions—if I even experience those—as I look down my nose and through my whiskers at the object of my obsession, my mission, indeed, my raison d’être. Sure it’s a bird, but we both know it’s more than that, and we each have our reasons. But in that moment, between my point and your shot, there is an existential conversation that you’re not really a part of. It’s between me and the bird.

I recall, for example, an exchange I had with a ringneck buried deep in the CRP grasses outside of Woonsocket, South Dakota. I had passed by the curmudgeonly old cock a number of times before my nose zeroed in on where he was holding tight. We were nose to beak, and all the world fell silent. There were no whistles, no barks, not even the swishing of the grass as the wind kept sweeping down the plains. There was just me and a philosophical pheasant.

His first question struck me as odd, but he asked, “Is this all there is?” His eyes were wide, with genuine curiosity instead of fear, and I offered the best response I could.

“If you mean will our lives be de-fined by this moment, then I have to tell you that I give you better-than-even odds. I’m pretty sure I’ll have puppies before these guys limit out today, and I’m male.” He offered a sheepish grin—though it was tough to discern on a pheasant’s beak—and chuckled at my response.

I poked my head up through the grass to see if anyone else had heard his chuckle, and returning, told him, “Brother, you better keep that down or you’ll get us both shot.” He took the criticism in stride and refocused his question.

“What I mean is, have we been held captive by instinct and biology, only to fall short of our respective potential as enlightened beings?” I was formulating a response when one of those wickedly enthusiastic English cockers busted up our little Algonquin Round Table, and that rooster flushed like a jet, leaving me with more questions than answers.

Toward the end of the next season, I was working a big spread of wiregrass outside of Moultrie, Georgia, when a strong scent wafted across my nose while I was in midair. By the time I hit the ground, my eyes and my cheeks were pointed in roughly the same direction. You do the math. As I unfurled the pretzel and eased my way toward the prize, I heard a whisper.

“Psst,” it said. “Over here, in the mouth of the old charred and hollow log.” My guns were still back at the Jeep, arguing over whose turn it was to miss, so I eased over to the log, only to find a Bob, leaning against the inside wall of the log like he was waiting on a slow bartender. I kept my nose to the ground but waved my tail slightly to downplay the hunters’ sense of urgency. Birdy, as they say, but not committed. “Do you find the prospect of intelligent design to be something of an intellectual cul-de-sac?” he asked, catching me off guard with an opening question of such depth. He seemed to notice my surprise and continued, “Given the circumstances, I thought we might dispense with the small talk.” I agreed with his assessment of the gravity of both the situation and the question.

I responded simply, “I see it as a theistic response to post-enlightenment scientific progress. Nothing more, nothing less.” He assimilated my response and countered with an even deeper probe.

“And if this entire panoply of lives is merely a hologram?” I had to shake my ears loose at the thought, and when I returned my snout to the stump, he was gone, without a trace, a flush, or a scent.

Upland hunting is always good for a little fellowship, a walk among friends, and a stroll among ideas. But who says the humans get to have all the fun?

—Frank