Dry conditions and decline in CRP a detriment to Texas pheasants

The near-term negative trend appears to continue for Texas pheasant populations as hunting season opens Saturday in the Panhandle.

“Over the last five to 10 years, we’ve definitely been in a lull,” said John McLaughlin, West Texas quail program leader for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

“The general trend right now is well below our long-term historic average and we’re in a cycle where we’ve had a couple consecutive years of poor rainfall. Much like quail this year we had hopes coming out of the winter, but as temperatures heated up over the summertime and we got into more drought-like conditions again, we saw a real suppression of nesting activity.”

TPWD’s annual roadside pheasant survey counted 90 birds this year, an average of 2.05 per route. The 2020 count was a slight drop from the 129 birds last year and a nudge above the dreary 62 from 2018. Altogether, a far cry from the 2,002 and 1,208 pheasant tallies of 2007 and 2010, respectively. The 10-year average is 115.2 birds.

he harsh drought that plagued the Southern U.S. and Mexico from 2010-13 marked the start of a stark downturn in Texas’ pheasant populations. Not only were pheasants negatively impacted by dry conditions and the emergency haying and grazing it induced, but the beginning of the decade saw a decline in Conservation Reserve Program acreage that has persisted through the present.

“That drought combined with a shift in CRP acreage really set us back,” McLaughlin said.

CRP is a Farm Service Agency program that incentivizes farmers to convert tracts of land from production to conservation by using native vegetation. In addition to providing habitat for upland game birds and other wildlife, CRP can reduce soil erosion and improve water quality.

The 2018 farm bill expanded the CRP acreage cap to 27 million by 2023, but that bill reduced rental rates, according to the Farm Bureau, which might have decreased interest in the program.

Texas’ ring-necked pheasant populations hinge on the conservation willingness of landowners who also must put food on the table and are bound by business decisions of their own. Restoring CRP acreage to the levels of previous decades is key to lifting pheasant populations. Though continuous sign-up is ongoing, the general enrollment period for 2021 runs Jan. 4 through Feb. 12. The CRP Grasslands enrollment is March 15 through April 23.

“In order for us to really get out of this lull we’re in, we need a couple consecutive years of quality rainfall and producers going into CRP and out of their normal crops,” McLaughlin said.

Dustin McNabb of Pheasants Forever, an organization that heavily promotes CRP, said that precision agriculture, which has revolutionized farming in the modern age with the advent of GPS and satellite technologies, is being used as an effective tool for conservation. Precision ag can identify unproductive sections of land that can be converted to cover vegetation for upland birds.

McNabb said changes in farming practices have also impacted pheasant populations.

Areas where cotton has become king do not provide the type of cover used by pheasants. The birds prefer crops like milo or corn.

“I can almost guarantee you that a sorghum field here on the South Plains or in the Panhandle is going to yield a bunch of pheasants, assuming that the nearby cover is what they like,” McNabb said.

He added that a monoculture of any type of vegetation isn’t optimal, either. The elimination of weedy field borders has been detrimental to pheasants and changes in technology have allowed crops to be harvested more intensively, reducing fallow periods for fields.

“For anyone who’s in wheat, we would encourage them to reduce post-harvest herbicide use and encourage them to plant varieties of wheat that grow taller. We do know that post-harvest stubble height is very important for pheasant habitat and retaining soil moisture,” McLaughlin added.

Despite the general population trend, spots of the Panhandle still hold promise for hunters this season. McLaughlin encourages hunters to be selective with harvest, although hunters do not negatively impact pheasant populations on a regional scale.

“Hunters didn’t cause the birds to decline to that historic low, it was a historic drought,” said Robert Perez, TPWD’s upland game bird program leader.

He noted that although bobwhite quail had banner years in the High Plains in 2015 and 2016, pheasants did not respond to the same degree. The TPWD survey counted 210 and 256 pheasants in those respective years.

Hope remains for an upswing in the future.

“The potential is there for that landscape to support more reliable, more dense population of pheasants,” said Perez.

“I just think we’ve had a series of unfortunate events.”

For those looking for a place to hunt, McNabb said a rule of thumb is the further north you go, the better the potential. He doesn’t see pheasants south of Lubbock or off the Caprock Escarpment.

A handful of locations are available on the public land hunting map in Floyd County, which historically have held pheasants.

“I wouldn’t be afraid to hunt it. Obviously, you need to scout it…But Floyd County, they typically have pretty good pheasant populations year in and year out. It won’t be phenomenal numbers, but if you’re looking for a place to go, that wouldn’t be a bad place to check out,” McNabb said.

McNabb also said that community hunts, like the ones done by the Chamber of Commerce in Olton or Lions Club in Cotton Center, can be a great introduction to Panhandle pheasant hunting. An organization like Pheasants Forever can help one get involved in conservation of the species as well as learn more about hunting in the region from fellow members.

Texas is a private-land state, though, and most pheasant hunting requires landowner permission. The Panhandle is one of the last bastions of the cultural relationship between landowner and hunter, where a knock on the door and respectful request can go a long way.

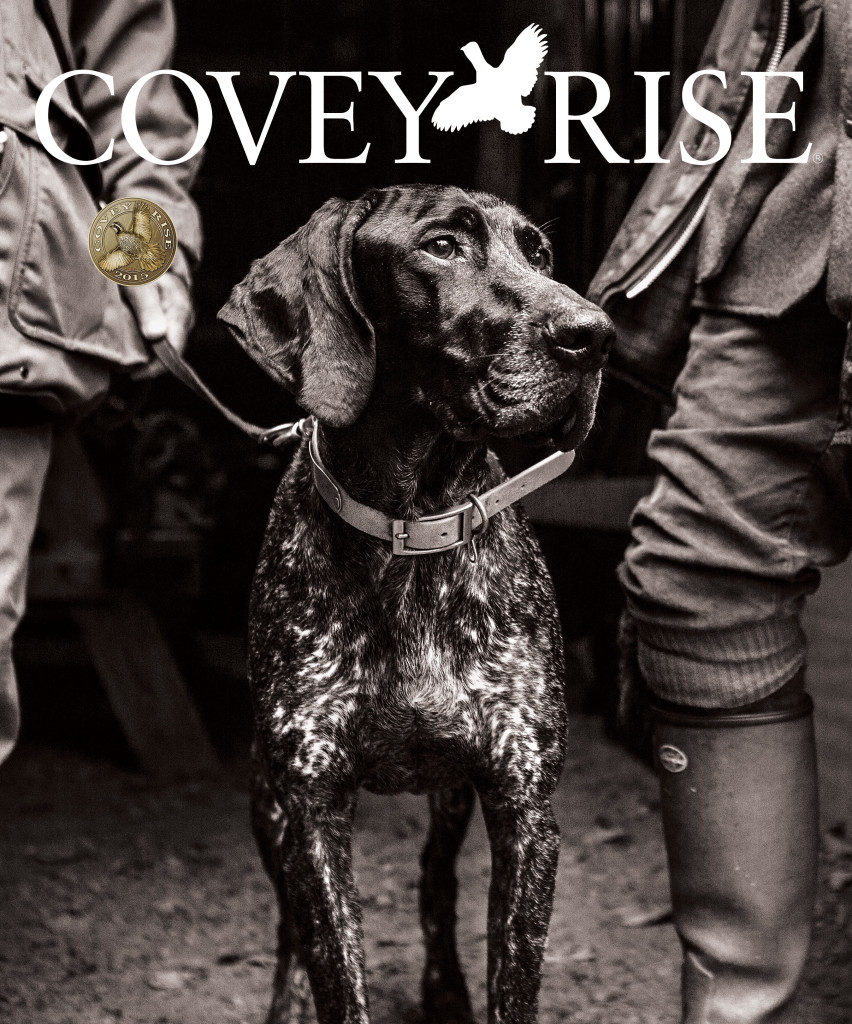

Regardless of harvest, chasing pheasants provides an experience of camaraderie with hunting partners, both human and canine. If nothing else, this year’s pheasant season gives another reason to go afield with friends.

“Find somebody that used to hunt. Find somebody that wants to hunt and may not have the resource or the ability to get somewhere. Or find a kid that’s interested and take them hunting,” McNabb said.

Pheasant season runs Saturday through Jan. 3 in 37 Panhandle counties. The daily bag limit is three cocks and proof of sex must be kept, which includes an attached leg with spur or the bird with entire plumage.

SHARE ON

You may also like

The role corn plays for gamebirds and economies ac...

Sportsmen’s conservation policy issues from publ...

Sportsmen’s conservation policy issues from publ...