BECOMING A COLLECTOR

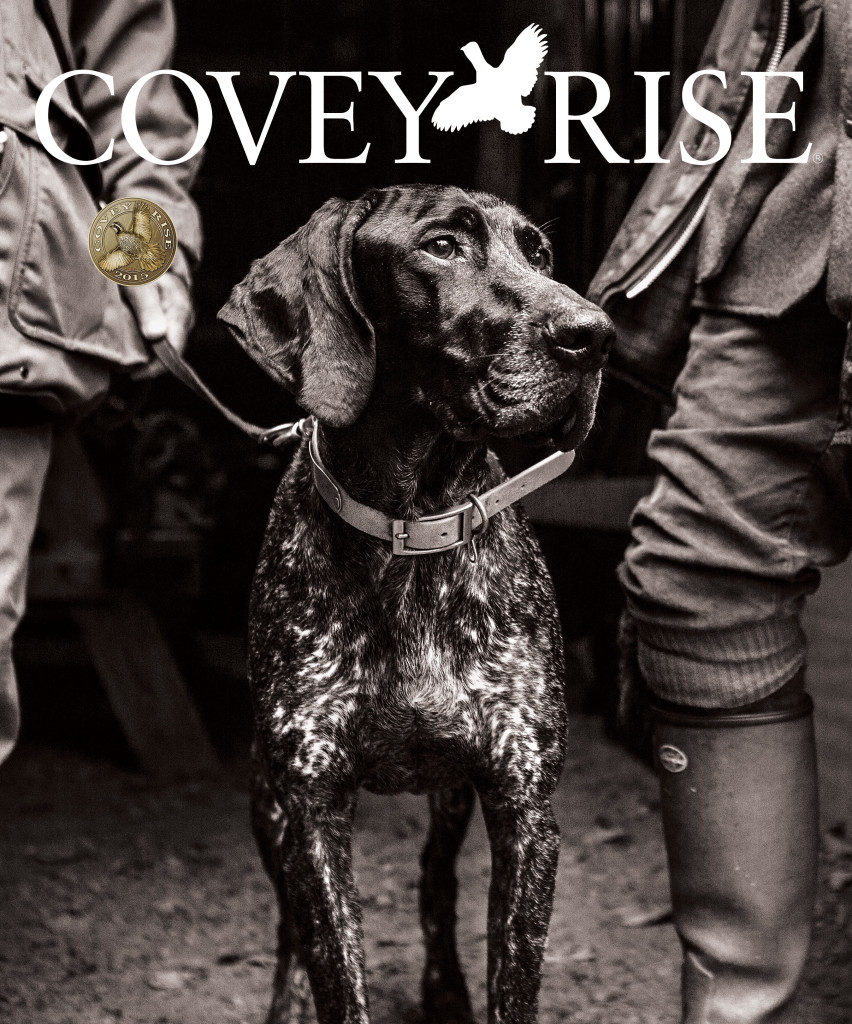

Story by Greggory Elliott and Photography by Terry Allen

Story originally published in Volume 3, Number 3

Here’s a short list of things I love: wild brook trout, snowstorms, wood-canvas canoes, pointers, and—of course—shotguns. For the past 30 years, I’ve been obsessed with shotguns. I’ve worked lousy jobs to buy them, flown across oceans to admire them, and walked away from promising careers to immerse myself in the study of them. I’ve contributed countless hours and thousands of dollars to this passion, and I don’t believe a single one has been misspent. Collecting fine, old shotguns has been one of the most rewarding activities of my life—and, in many ways, one of the most revealing.

Day to day, I’m surrounded by shotguns. As I write this, books and magazines about side-by-sides and over-and-unders are all around me—multivolume sets outlining the evolution of their design, a thigh-high stack of Double Gun Journal magazines, a pillar of gunmaker histories, and on and on. Then there are the actual firearms. I keep one double close by for admiring. Today, it’s a 12-gauge William Powell & Son hammergun built in 1869 for a “Captain Cave.” Who was this Captain? What did he see? Even though we live more than a century apart, in different worlds, we’ve met through this gun (if only spiritually, perhaps). Its metal buttplate has touched his shoulder and mine. Our hands have wrapped around the stocks and our fingers have reached for the front trigger. Did the Captain carry our Powell to the grouse moors of Scotland? Did he take it to pheasant shoots on an English estate? All is lost to history, but wondering about it is one of the greatest pleasures I get from old shotguns.

I’ve owned dozens of shotguns over the past three decades. A 20-gauge Remington pump was my first. I bought it when I was 14 with money I earned by flipping burgers. I loved that gun because it had a straight, English stock. But the same as most of my shotguns, I sold it when something better came along. This time it was a 16-gauge Winchester Model 12. That gun had 80-plus years of wear on it and I loved the rubbed-away blueing and dinged stock. Since the Model 12, I’ve owned Parkers, Foxes, and L. C. Smiths, British sidelocks, Belgian side-by-sides, and Italian over-and-unders. Some I traded away after a few days; others have been with me for decades. As I’ve done this, I’ve gone from being a shotgun accumulator to a shotgun collector.

Like dogs in heat, accumulators have low standards—or at least I did when I was one. If a shotgun had two barrels and a couple triggers, I wanted it. A Parker with sawed-off barrels, rattly British boxlocks, an Ithaca pimpled with rust—I bought them all and traded them away when something else came along. Along the way, I picked up a few I couldn’t bear to sell: a W. & C. Scott Premier, a W. W. Greener FH 35, a Super Fox, and Captain Cave’s Powell. These guns had something I couldn’t part with. As I realized this, I became a collector.

Collectors know what they want—or at least they have a better idea of what they’re looking for than accumulators do. Most focus on a single maker, such as A. H. Fox or Lefever. Others collect early centerfire or hammerless models. My parameters are still pretty broad. I like old doubles—Pre–World War I is nice, guns from the 19th Century are better. I also like Damascus barrels and double triggers. I used to prefer straight stocks, but these days I’m okay with round-knob or half-pistol grips. British and European shotguns interest me most, but there’s a Parker DHE on the market right now that keeps tugging at me. I feel I need to own it, and I’ll probably do my best to buy it.

As I made my way from accumulating to collecting, I made a lot of mistakes. I learned a few lessons, too. I can help save you from following me down the same path. If you’re thinking about starting a shotgun collection, start with some important considerations:

DISCOVER WHAT MATTERS TO YOU Gun collecting is a bit like growing up: You begin with what others say is important; then you figure out what’s important to you. Parkers are the most collected shotguns in America, and the high-grade ones are more coveted than great grouse dogs or pinelands full of wild quail. Several years ago, I handled the highest-grade Parker ever made—an Invincible. For some collectors, this would have been a holy moment. Not for me. Although I appreciated what I was seeing, my heart didn’t skip a beat. I have the same reaction to super-expensive Italian shotguns. Even F.lli Rizzinis and Fabbris—althought they are supposed to be the finest doubles ever made, every one I’ve seen has made me yawn. A low-grade L. C. Smith I owned a couple years ago thrilled me more. You may feel differently, and to build a collection that means something. Follow that feeling.

TRY TO STICK TO SHOTGUNS IN ALL-ORIGINAL CONDITION By all original I mean guns with their original blueing, blacking, color-case-hardening, and wood finishes. There are a lot of refinished and restored shotguns on the market today—but like pen-raised pheasants, they’re not the same as their original cousins.

Refinished and restored shotguns may look okay, but they don’t hold their value as well as comparable ones in all-original condition. If I’m going to spend thousands of dollars on a side-by-side, I want to know I can sell it and get my money back. Making a little extra would be even better. With doubles in all-original condition, you stand a better chance of this happening.

Refinished and restored shotguns don’t hold as much meaning for me, either. The thing I love most about old doubles is their history, and a double’s original finish is a crucial part of that history. It was put there by men who lived in another time, and touching it connects me to their history. Also, I like the dings, scrapes, and scratches you find on old shotguns—which give authenticity and character, and contribute to the story of the gun’s life. I want to leave that story intact and, as the gun’s latest owner and steward, add my own chapter to that history.

DO MORE LEARNING THAN BUYING When it comes to collecting, books are cheap and knowledge is priceless. So build up your library. If you’re new to doubles, McIntosh’s Shotguns & Shooting is a good place to begin. If you’re interested in British guns, Burrard’s The Modern Shotgun and Hadoke’s Vintage Guns for the Modern Shot will tell you what sets guns apart and what to look for when buying them. All the major American and British makers have had books written about them. All are worth reading.

Of course, as you’re learning, you also want to see as many side-by-sides and over-and-unders as possible. While the Internet is a great way to do this, nothing compares to having a gun in hand. To make this happen, you can visit gun dealers. But those who specialize in fine shotguns are spread thin around the country. So think about visiting high-end gun shows, instead. Most of the major gun dealers attend the Las Vegas International Sporting Arms Show, the Vintage Cup Exhibition, or the Southern Side-by-Side. You can see hundreds of nice shotguns, in one place, at these shows, from Fox Sterlingworths to Holland & Holland Royals. You’ll get a great education.

GET ACQUAINTED WITH THE PRICES To get a feel for what nice shotguns are selling for, check websites like gunsinternational.com. But know this: Most of those prices are asking prices. Haggling is a part of the gun-buying game, and to account for this sporting gamesmanship, most dealers add a little room to their prices. What this means is, don’t be reluctant to make an offer on a gun, and don’t hesitate to walk away if the seller says no. Unless a double is spectacular—and few really are—I would rather have cash in the bank than too much money in one gun.

MAKE FRIENDS WITH A GOOD GUNSMITH A gunsmith should inspect every shotgun you’re thinking about buying—before you close the deal. Ask around and find one who works on old side-by-sides and over-and-unders all the time. Of course, your gunsmith will charge you for this service. But it will be money well spent, and if you can be there when your ’smith is looking over the gun, you can learn a lot about doubles.

Several years ago I came across a 12-gauge hammerless Purdey at a fair price. The gun was online, and I was in touch with the seller within minutes of seeing it. He sent me plenty of pictures. I looked for all the right things and asked all the right questions. I even contacted Purdey in London to confirm the gun’s original specs. From what I could tell, the gun was a go, and I was ecstatic. So I sent the check, and the Purdey was sent to my gunsmith. It arrived at his shop a few days later. Within minutes of looking it over, he spotted a major problem and got on the phone to tell me about it: The barrels had been replaced, and not by Purdey. What!? How did I make such a huge mistake? Because whoever replaced the barrels had done a great job of making the new ones look original. The giveaways were small—just a few missing proof marks on the barrels—but the impact was enormous. Now the gun wasn’t a collectible double at a good price—it was just an overpriced shooter. So back it went for a refund. Although the whole experience cost me a couple hundred dollars, my gunsmith saved me from wasting thousands of dollars more.

BE WARY OF AUCTIONS Back when I first got into doubles, a newspaper called Antiques and the Arts Weekly was my favorite publication. Each edition published hundreds of listings for upcoming auctions throughout the Northeast. I scanned each one with ink-stained fingers and tired eyes, searching for used shotguns. Back then, few auctioneers had websites or even email addresses. So when I found something, the only way to see it was to jump in my truck and go to it in person.

Today, you can go on the Internet and search hundreds of auction listings in minutes. When you find a double that looks nice, you can bid for it online. A collector’s dream, right? Not really. Auctions have always been buyer-beware situations. Today, that’s more true than ever. While you can find bargains at auctions, you can also get burned.

Here’s the problem: Every auction is a gamble, and when you’re bidding online, you’re the one taking all the risk. Few auctioneers are experienced with fine shotguns. While most can tell you basic information like gauges and barrel lengths, almost none know crucial details like bore measurements and barrel-wall thicknesses. On top of this, few auctioneers guarantee their descriptions or that the information is accurate or even correct. (I’m not kidding—check the small print.) So if you’re the winning bidder on a shotgun, you own it, regardless what kind of condition it’s really in. This is how you can end up paying $5,000 for a double that’s really worth $2,500—or even less.

Of course, there are smart ways to bid on shotguns at auctions. The first is to show up, inspect everything you’re interested in buying, and stay to bid on it yourself. The second is to hire someone to do this for you. If you’re new to doubles, option two is the only way to go.

Most important of all, enjoy yourself. As you learn more about shotguns, visit shows, and start a collection—have fun. Don’t ever feel pressured to buy something. I’ve missed out on all sorts of doubles—an 8-gauge J. D. Dougall, a straight-gripped Parker DHE, some great British boxlocks—mainly because I was broke when they became available. That used to eat at me. Today, I barely think about it. Great shotguns come up all the time—I know another “must-have” will be along soon. You will make mistakes, you will buy bad guns, and you will end up losing some money. But you will also meet great people, see some fantastic doubles, and find out a little more about what’s important to you. And that’s what makes collecting shotguns so special.

As I made my way from accumulating to collecting, I made a lot of mistakes. I learned a few lessons, too. I can help save you from following me down the same path.