Why We Burn

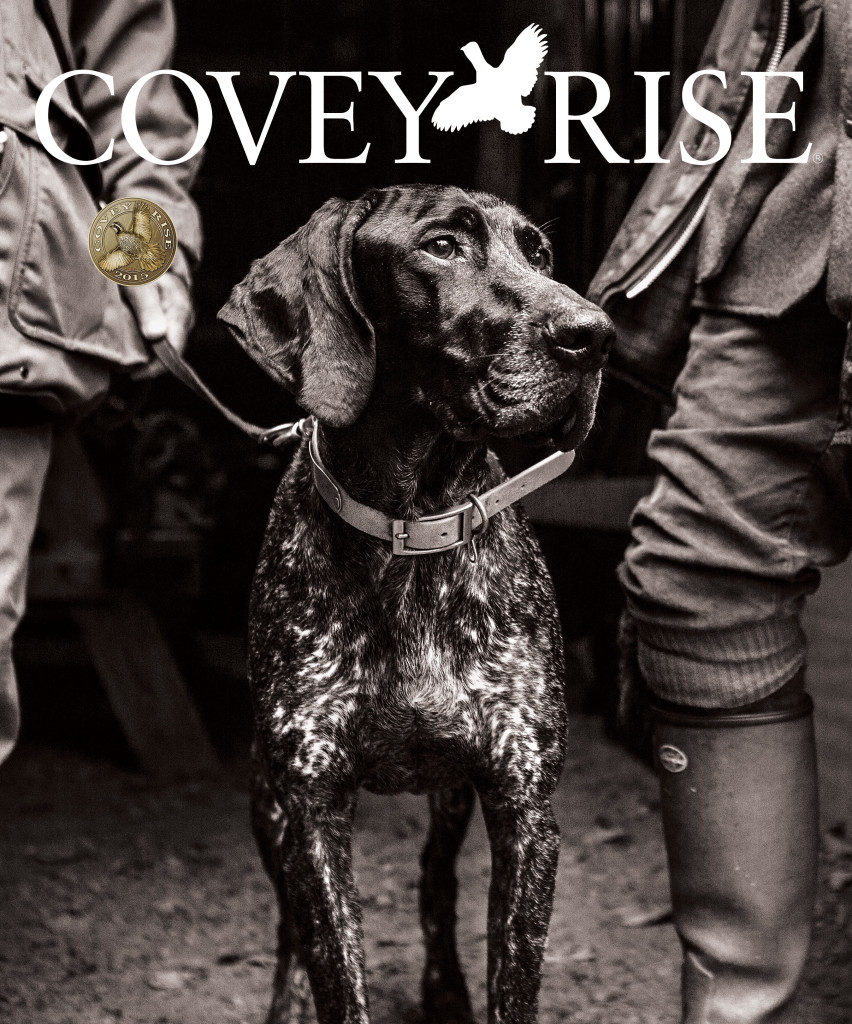

An excerpt…Walking a freshly turned firebreak, I was dripping a diesel-and-gasoline cocktail along the edge of planted pines when an Eastern hognose snake bumped the tip of my torch with an inquisitive glance, its body extending from the brush like a gleaming staff of carbon fiber. Snake is not a second language for me, but he seemed to be asking why I was setting fire to his woods on such a crisp winter’s day and would I mind moving along so that he could scare up a little lunch. Happy to oblige, I cast my fire to the end of the lane, set down my torch and, in a strange, existential twist, considered these questions: Why do we set the woods on fire and why does it ignite in us a fascination as primitive as the snake itself?

Simply put, prescribed burning replicates one of nature’s most essential grooming tools, spreading fire across a forest floor, eliminating the competition for target species, and renewing soil with essential nutrients to encourage native growth. Humans have replaced nature’s random lightning strike with the more predictable drip torch, but the awe and ferocity of fire is the same. We manage the enterprise as best we can, cutting in firebreaks and choosing days or nights when the wind, relative humidity, and dispersion indexes are most favorable. We burn in rotations that allow fuel to reach a combustible but manageable level, sufficient to knock back the undergrowth without damaging the desired trees such as pines, which have evolved with thick, protective bark and thrive in fiery conditions.

Trees, however, aren’t the only beneficiaries. Scratchers like quail and wild turkeys will often begin the quest for bugs even before the smoke clears, while predatory hawks and coyotes quickly follow a fire to enjoy a brief window of better hunting as the food chain resets and balances. Within days, new native growth emerges, resulting in fresh greenery for the deer and other grazers. Also bouncing back quickly are the hedgerows and broom straw that shelter quail and other species as the forest floor shifts from the grays and blacks of smoke and ash to the brilliant greens and golds that draw us afield with dogs and friends and stories new and old.

SHARE ON

You may also like

The role corn plays for gamebirds and economies ac...

Sportsmen’s conservation policy issues from publ...

Sportsmen’s conservation policy issues from publ...